Contemplating Authenticity in A Hidden Life

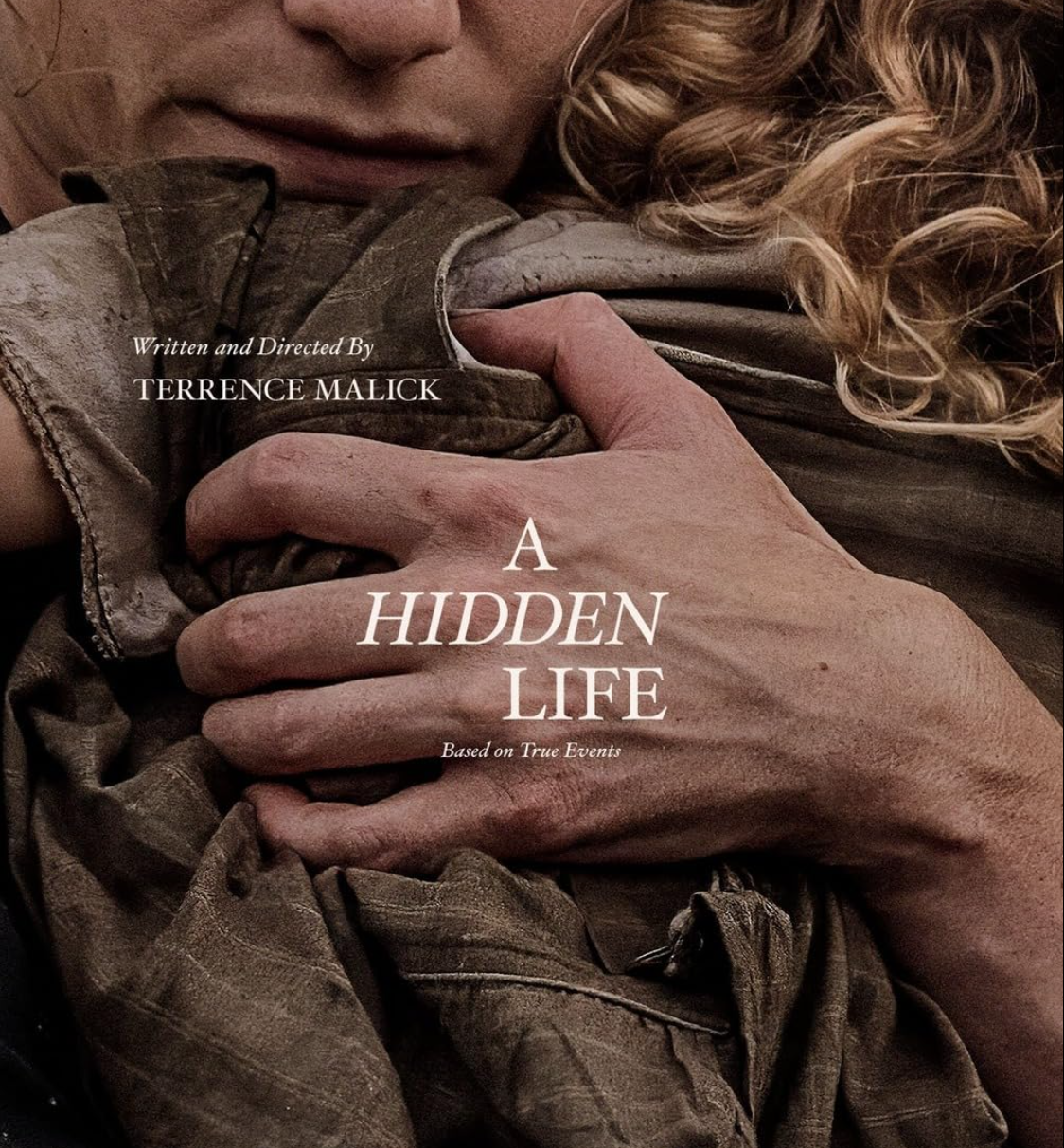

In the 2019 film A Hidden Life, director Terrence Malick deviates from the unique “phenomenological” style that radically abandoned coherent narrative logic, which began with The Tree of Life, and returns to a World War II theme for the first time in over two decades since The Thin Red Line. This time, Malick employs a more traditional story structure to recount the tragic tale of an Austrian farmer executed for refusing to pledge unconditional allegiance to Hitler during World War II. Although the plot is adapted from a true historical event, in keeping with Malick’s previous films, it weaves philosophical explorations of the meaning of human existence into its “poetic” artistic style.

In the context of contemporary “postmodern” society, grand narratives with heroic overtones are diminishing, and notions of the sublime are often deconstructed. Even heroic stories based on historical truths face new challenges. Placing characters within contemporary ideological currents to interrogate their morality and situating values within difficult circumstances are the very issues contemporary cinema must confront. This paper attempts to interpret A Hidden Life through the concept of “authenticity,” arguing that the director’s portrayal and evaluation of authenticity are central to understanding this film.

Keywords: Terrence Malick, World War II, Authenticity, Existentialism, Auteur Cinema

The Concept of Authenticity and the Protagonist’s Authenticity

The term “authenticity” derives from the Greek “authentes”, which is composed of the prefix “autos” (self, automatic) and “entes” (achieving, realizing). Etymologically, it connotes something that is “real, genuine, and not a counterfeit or copy” with an attribute of “original authorship” (Webster’s Revised Unabridged Dictionary). The philosophical notion of authenticity entered mainstream discourse largely due to its use in translating Heidegger’s 1927 work Being and Time, where he coined the term “Eigentlichkeit” to denote a kind of “ownedness” of one’s existence and actions. This “ownedness”, as Heidegger’s most comprehensive conception of human realization, stems from his idea of “Dasein” (being-there). Human Dasein involves the disclosure and unfolding of life into an open realm of possibilities; authenticity thus lies in understanding the relationship between the limited possibilities imposed by our “thrownness” and the purposefulness of our life projects. Authenticity’s call to “be true to oneself, to one’s own potentialities” becomes an ongoing pursuit. It is an indispensable character trait that emerges after grappling with the identity crises of anxiety, death, and conscience - a refusal to succumb to a life of “fallenness”, instead grasping onto self-construction, embodying self-sovereignty, seeking truth, and realizing a rational, valuable existence.

Contemporary understandings of authenticity hinge on individual self-realization, reflecting a historical shift from conceiving the self as part of a larger social whole towards an independent individual entity. The demand that each person be responsible for their own actions, privileging individual will over social responsibility, is considered by some historians as an ahistorical, constructed understanding. However, authenticity’s core of being “true to” an intended purpose that is the action itself is an ancient concept. Authenticity, as an ethical flourishing, originates from a subversive moral construction process, breaking ground from a transcendent divine paradigm, signifying the internalization of moral sovereignty from external judgment. “No longer in contact with God or the concept of good, we now find that source deeply embedded within ourselves,” a shift vividly termed by Charles Taylor as “the displacement of moral accent,” with abundant examples from Renaissance art. This “inward turn” has variants – a pantheistic direction like Rousseau’s popular sovereignty expressing positive freedom through social contract theory, and another towards individualism. Authenticity itself is a virtue akin to perseverance, courage, and diligence. From a Kantian moral framework, authenticity undoubtedly falls under the category of the supreme moral law’s universal imperative, for its absence would undermine the distinction between rationality and irrationality. Yet it should not exist alone. While its two variants elevate authenticity as an supreme ethical ideal of self-realization, even the telos of contemporary life – a countermovement against the totalizing ideological forces of the two World Wars and the Cold War – rooted in recognizing and respecting differences, everyone has an indisputable lifestyle, a highly personalized measure of the world, signifying a unique “way of being” in the world. This individualized measure, understanding and determining the world’s values and rules, is central to embodying “self” and differentiating from “others,” negating any transcendent, authoritative measures and directly challenging Hegel’s advocacy for moral life within community-led norms. Realizing “my way” according to “my measure” in real life is the true manifestation of “my existence.” Authenticity, encompassing self-awareness, bridges the individual with the world, including dimensions beyond “self.” Self-discovery through careful observation and reflection implies authenticity as a world exploration. Otherwise, emphasizing internal ethics risks descending into self-indulgence and narcissism. For example, adhering to authenticity’s emphasis on being true to oneself, can one practice blatantly immoral human inclinations without reservation? Hegel’s critique of Kant’s moral theory as “empty formalism” reflects skepticism towards purely rational moral objectives. The contemporary Western cultural shift, making authenticity a goal rather than a means, leading to narrowness and mediocrity, has become a critical focus for many scholars (Taylor 1992; Patterson 2006; Bloom 1987).

The film A Hidden Life, through depicting the era’s tragedy of an ordinary man, in fact proffers a different understanding of authenticity: perhaps it was the lack of the protagonist’s conception of an “individual-world” authenticity among the Nazi majority that caused the self to recede into a mere social placeholder, constricting the open realm of human possibility to the lowest common denominator of society. This impaired self-perception and undermined the cultivation of public morality and rational social construction. In an extreme era, waning self-knowledge evolved into a nihilistic obsession with collective power, rendering the unimaginable evils possible by collapsing social rationality into a purely instrumental understanding. This is an attempt to analyze how the director dramatizes this premise through the film itself.

The contemplation of “individual-world” authenticity in the film manifests across multiple dimensions. From the screenplay perspective, a core question the film must address is why the protagonist, Franz, pays a heavy price to refuse the oath. If such resistance is futile, fruitless, unknown, and soon forgotten, does the act still hold importance? The director unequivocally answers no, asserting that judging the morality of a process by its outcome is absurd. Franz, an Austrian farmer drawn into the German army due to the annexation of Austria during World War II, steadfastly refuses to swear allegiance, a decision personal and uncoerced, spotlighting the film’s inquiry into the origins of Franz’s authenticity. In this aspect, the film aligns with Hegel’s critique of Kant’s rational morality by negating the a priori formation of moral views, yet diverging from Hegel’s moral community (Sittlichkeit), it explores individual moral spaces’ critical limits or reshaping of moral communities. This moral stance diverges from Kant’s morality, detached from social customs and life experiences, and aligns more closely with Heidegger’s interpretation of authenticity, where authenticity is not merely loyalty to the self but is integrated with one’s “thrownness” into the world, forming the basis of rationality.

The first act of the film mainly introduces Franz’s natural and social environments, illustrating his refusal to join the nascent radical social movement shaped by his self-awareness and traditional moral views, ultimately leading to his refusal to swear allegiance to Hitler personally. This refusal stems from his questioning of the war’s morality, disdain for Hitler, and his religious beliefs. Director Malick, to underscore Franz’s formation of personal measure of authenticity, extensively portrays how Franz, through military training, conversations with others, labour, connection with nature, and his religious faith, develops his questioning and revulsion towards the war initiated by Germany. Franz’s stance towards Hitler encompasses broader issues, including Germany’s racial policies and a deeply religious moral judgement. The film highlights Franz and other dissenters of Nazi policies as marginalized figures in Austrian society at the time, illustrating mainstream society’s confusion or anger towards Franz’s actions. Notably, unlike films like The Sound of Music, which also depict the era, A Hidden Life largely avoids discussing the impact of Austria’s annexation by Germany on Franz’s national identity, indicating Malick’s intent to present Franz primarily as a symbol of resistance against societal control.

Authenticity, as a moral attribute, requires the capacity for bias-free self-reflection, clear insight into one’s level of self-awareness, and identity formation based on a comprehensive understanding of the complex relationship between oneself and the surrounding world. Essentially, since human self is always intertwined with the public world, authenticity must encompass social responsibility, fulfilment, and cooperation rather than conflict. Franz’s self-awareness is rooted in his environment, not purely from rational thought. Becoming authentic is an ongoing process, not a singular event, reflecting not only self-understanding but also awareness of others and mutual influences. He establishes a basic moral compass based on daily farming labour, family upkeep, and public life, a focus on environmental sensory experience validated by Malick’s detailed depiction of Austrian rural life. As Saint Augustine said, the path to God is through our consciousness of ourselves. The political movements and war mobilization activities in Radegund also continuously provide new foundations for Franz’s self-awareness. Franz’s decision to refuse the oath is not abrupt but well-considered, suggesting authenticity doesn’t necessarily need to be publicly displayed at all times, as indicated by the concepts of internal and external authenticity. Sometimes, to avoid burdening others, people may choose to conceal their self-awareness. Before being conscripted, Franz did not disclose his intention to refuse the oath except to his wife, who understood his pursuit of an authentic life and foresaw the abyss he would enter. In the societal context of the time, Franz’s refusal to accept war veteran pensions, donate to the war effort, or rebuke greetings in Hitler’s name already provoked hostility from his community, subjecting him to significant social pressure. Why Franz could remain “true to himself” poses another question to be addressed. Authenticity requires distinguishing what is true, false, logical, and illogical. The film validates this distinction through Franz’s Christian faith, influenced by sermons, hypocritical followers, and dissenters within the church discussing Hitler’s actions from an anti-Christ perspective, directly impacting Franz. However, the film shows the church’s weakness and submission during the Nazi era, indicating Franz’s internal moral judgment as the main factor influencing his actions, not the call of an external religious institution. The film clearly shows a plethora of inauthentic attitudes and understandings of authenticity in society at the time. The town priest, when Franz seeks help, shows a complex mix of sympathy, understanding, regret, advisement, and powerlessness, reminding Franz of the limited practical significance of his actions and the high cost to his family and himself. When Franz seeks assistance from the bishop, the bishop reluctantly tells him that he should be loyal to the nation and its leader, a duty derived from his civic identity. The townspeople’s troubles for Franz’s family can also be seen as a condemnation of Franz’s pursuit of personal faith over his responsibilities in real life as a husband and community member, highlighting a stark clash between authenticity and inauthenticity. Authenticity’s key feature is to strip away constructions and distortions in self-thought and behavior caused by social pressure, whereas inauthenticity represents another mode of existence. In the film, authenticity and inauthenticity coexist in the same spacetime, forming a complementary rather than antagonistic relationship. The film’s stance is not to criticize those who dissembled, played along, or preserved their lives under Nazi rule, but to emphasize the necessity and universality of living inauthentically under the crushing public will governed by nationalism and statism during extreme times, thereby highlighting the value of achieving authenticity.

the village during the war

the village during the war

The latter half of the film’s plot is divided between Franz and his wife, depicting the cost of maintaining authenticity. Franz suffers in prison, with shots of windows symbolizing the contrast between freedom and imprisonment, while his wife endures hardships in the countryside due to lack of labour and hostility. Here, authenticity becomes the source of all suffering. To refute Franz’s authenticity and persuade him towards an inauthentic life, the film selects scenes with a Nazi prosecutor, defense attorney, and military court judge questioning Franz’s authenticity from perspectives of ideological interrogation, practical benefits, and legal tradition. The prosecutor’s dialogue is particularly significant, questioning the essence of Franz’s maintained authenticity. Does authenticity imply intellectual superiority? Is it a form of arrogant pride? Does the distinction between good and evil stem from some form of agnosticism? Should authenticity consider the realities of survival? The prosecutor’s questioning suggests the protagonist lacks the intellectual and authoritative capacity for rational judgment of justice and injustice. Franz provides his own answer: he believes making moral judgments is his duty as an individual, and following these standards to avoid evil acts is his corresponding right as a human being, valuing the freedom of the soul over physical imprisonment. Franz views civic duty as predicated on mutual recognition between the state and citizens; from a social responsibility perspective, conscription impedes his family duties as a father and son, explicitly negates his personal religious faith, and importantly, family survival or community support does not exempt one from original sin. The film’s interpretation of authenticity highlights a freedom of refusal, the liberty to set and follow one’s own values and rules as the sole condition for self-approval. If authenticity is indeed possible, then “self” must be understood as capable of changing norms. Authenticity should hold the same imperative in moral commandments as rational thought. Franz’s response also addresses common critiques of authenticity head-on. More significantly, Franz demonstrates a higher understanding of authenticity: it grants his life meaning, serving as an antidote to the absurdity and nihilism brought about by being “thrown” into existence. The film’s emphasis on family bonds and the protagonist’s positive attitude toward life clearly illustrates Franz is not a hermit fleeing real life but is pursuing a morally consistent authentic existence.

Malick’s Cinematic Language of Authenticity

Malick’s unique visual style, characterized by continuous interaction between the camera and characters/scenes, forms a distinctive cinematic language. Rather than using fixed positions, the camera maintains a mysterious and subtle motion relative to close-up characters, and the use of wide-angle lenses with edge distortion gives the shots an omnipresent sense of “intrusion” and “closeness.” This approach transforms the audience’s role from neutral observers to immersive participants, moving with the protagonist as if freely flying through all scenes while staying close to the central figure. The camera’s roaming movement, consistently low angles, and upward shots of characters provide a novel, non-human perspective, offering a poetic yet realistic observation of life in the depicted era for the audience. The combination of voiceovers, music, and imagery, maintaining a separate but connected progression, is a stylistic hallmark Malick developed since his first film Badlands. This style not only serves as an artistic expression for specific scenes but has become predominant, especially in films like Song to Song and Knight of Cups. A Hidden Life is no exception, but this style, placed within the context of the characters and their world, not only fits but generates new meanings. All of Malick’s historical films, from Badlands to Days of Heaven, The Thin Red Line, and The New World, are philosophical meditations on the nature of human interaction with nature, moral experience, and love. The discussion of authenticity in this film centres on the relationship between humans and the world, and the legitimacy of intrinsic measures. Heidegger spoke of the need to consider the “worlding” of the world in human existence, where “world” is a verb, specifically referring to the series of relationships constructed between humans and the world in existence. Malick’s cinematography becomes a brilliant tool for exploring this foundational premise of authenticity, even surpassing the expressive limits of language. For instance, Franz’s introduction in the film clearly demonstrates this intrinsic relationship. When Franz first appears, his back to the camera, facing his work in the fields against the backdrop of towering mountains, the scene creates a deep depth of field. The director uses wide-angle lenses to naturally place the vast mountains and foreground Franz together, ensuring both foreground and background are in focus for the audience, creating an equal, integrated visual narrative of man and nature.

Franz with nature

Franz with nature

Additionally, the director deliberately mixes various sounds from the recreated historical scenes, creating a unique emphasis on both the objective world of the film and the characters’ perceived world. Human activities in the film are scaled down according to the dimensions of the natural world, implying that humans and nature presented in the film exist on equal terms, interconnected and complementary. This scaling, even explored at the higher dimensions of cosmic space in films like The Tree of Life and Voyage of Time, is vividly rendered through recurring inserts of rushing rivers, towering mountains, imposing clouds, and dense forests, fully portraying the scale contrast between humans and nature. Malick posits that humans must be understood within a larger temporal and spatial dimension, not confined to human history. This stance further implies that if the measure of good and evil is entirely internal to the individual, it is inherently absurd.

The frequent insertion of natural landscapes amidst human activity in the film is not merely for variety or scene setting but forms a Malick-style natural world montage. This style, once humorously dubbed the “Discovery Channel” approach, actually emphasizes Malick’s continuous focus on the relationship between humans and nature. As humanity progresses towards modernity, the relationship between humans and nature evolves from a harmonious unity of “man-God-nature” to an emphasis on the self and the human species. Human-centricism, by extracting humans from the natural society, completes the detachment from the cosmic order. This detachment is inseparable from the changing concept of self, with authenticity closely linked to this change. However, this detachment ultimately leads to a return to collective consciousness. When Rousseau uses subjective freedom to emphasize public liberty, hints of authoritarianism emerge. The individual’s detachment from the “man-God-society” relationship becomes the prerequisite for the rise of nation-states replacing “God.” The re-embedding of individuals in the shifting relationships between man and society effectively counters the tendency to detach from “self” and naturally suppresses authenticity, as depicted in Nazi Germany during WWII. When the emphasis on “self” value becomes indifference to and concession from public politics, moving from “God’s world” to “the world of nature” and then to “the objectification of nature,” the resulting vacuum in the new public space is filled by the ruling minority. The pursuit and practice of ethical authenticity require a transcendent form of self (the construction of “self” requires transcending the understanding of “self”) to balance this detachment. Therefore, in this imbalanced environment, the formation of public morals in various aspects lacks diversity due to modernism’s exalted “self,” inevitably leading to deviation from ethical authenticity. Concerned about this relationship, Malick attempts to reconnect authenticity with the natural world. He uses the protagonist’s actions to rethink the relationship between humans, nature, and society. The use of following shots in the film is a prominent example. When the protagonist walks away from the camera towards the background, the camera effectively engages in an alternative exploration. By turning away from the protagonist, the camera de-emphasizes the protagonist’s facial expressions, relegating the protagonist’s subjective feelings to a secondary position, instead adopting a perspective outside the protagonist to observe, placing the protagonist within the observed environment. When the protagonist views mountains, rivers, grasslands, trees, towns, or other people, the film invites the audience to join the protagonist in contemplating the relationship between people and their world during the war era. In this sense, A Hidden Life resembles Malick’s contemplation of war in The Thin Red Line from the late 90s, offering a grand perspective on human war activities as an overview and critique.

Franz riding a motorcycle

Franz riding a motorcycle

This perspective, especially during scenes depicting the protagonist’s suffering, even employs a first-person viewpoint to directly replace the audience’s observational perspective. Seeing foreign homes destroyed, unwilling soldiers becoming wild men in the woods, and discovering people around filled with xenophobic nationalist fervor, do we, like the protagonist, consciously strip away the distorted influence of the current view and adhere to our own moral standards? When viewed from a first-person perspective, being beaten and tortured by guards, staggering towards the guillotine, do we have the courage to persist? Meanwhile, the film’s extensive use of jump cuts, even continuous fragmentation within the same set of shots to disrupt narrative continuity, emphasizes the effect of estrangement, deliberately conveying a fragmented reality to the audience, deepening their contemplation of the essence of life created by the film.

The film’s sound effects also play a crucial role in shaping this exploration. The emphasis on environmental sounds permeates the film in a surrealistic manner. For example, in the idyllic Austrian countryside, the sounds of cowbells and wind often appear simultaneously in different scenes with unrealistically loud volumes, forming a new mood that transcends the visual, distinct from the author’s customary voiceover monologues, allowing the audience to experience a transcendence of human sensory capabilities. The opening scenes featuring Hitler’s Triumph of the Will parade with airplanes, and the pivotal scene breaking the rural tranquility—Franz’s wife Fani hearing the roar of planes and looking up—mirror each other. Symbols of industrial civilization, such as planes and trains, appear as forces compelling submission. The director specifically bridges historical footage with filmed scenes to represent the overwhelming power of modern industrial civilization over humans, seemingly suggesting modernity drags and races in a form detached from natural human laws.

Authenticity Emanating from Real Historical Imagery

Another subtle reflection on authenticity is the pointed use of Hitler’s personal historical footage. In a sense, Hitler’s interactions with children and dancing with guests, interspersed among Franz’s pastoral life scenes, create a brilliant contrast. These rare glimpses into Hitler’s personal life nearly diminish the authenticity portrayed by actors in the film. Hitler, a political figure adept at public performance, reveals a certain authenticity only in these highly private life scenes. It’s as if the film suggests that authentic life exists even in Hitler, a villainous politician, just as a guard menacingly staring at Franz one moment dances like a child on the street the next. Both authenticity and inauthenticity are states accessible to everyone, with inauthenticity becoming the unnoticed everydayness. Through these portrayals, the director ultimately affirms the meaning of Franz’s authenticity through his wife Fani’s words: “One day, people will know what this was for.” This leads to the film’s final scene quoting George Eliot’s closing passage from Middlemarch:

for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts, and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.

Clearly, the Franzes are not unnoticed. Their adherence to their authenticity is recognized by future generations and immortalized by Malick’s film, circulating worldwide. A Hidden Life embodies the idea that authentic living is not an extreme expression of individualism but an ordinary life under the world’s multiple identities. The existence of this type of authenticity in the film becomes a profoundly important constraint and counter to potential extremes of evil, “making things not so ill with you and me.”

References

[1] M. Heidegger, “Being and Time,” Philos. Altern., vol. 11, no. 2, p. 16, 1996.

[2] C. Taylor, The malaise of modernity. 1991.

[3] U. Steinvorth, A secular absolute: How modern philosophy discovered authenticity. 2020.

[4] C. Guignon, “Authenticity,” vol. 2, pp. 277–290, 2008.

[5] B. G. Yacobi, “The Limits of Authenticity,” Philos. Now, 2012.

[6] Finn, “Franz Jägerstätter as social critic,” Glob. Discourse, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 286–296, 2015, doi: 10.1080/23269995.2015.1018665.

[7] J.-P. Sartre, “L’être et le néant.” 1943.

[8] T. Malick, Terecen Malick Film and Philosophy. .

(Abridged version was originally published in 2021)